This is the second part in a four part series called The Road to Consumer Nationalism. Part 1

2

3

.

After the 2016 election, TV ads became unmoored from the products they purported to sell. We all noticed it. Budweiser abandoned its Super Bowl Clydesdales for sappy, utterly fabricated schlock

about the immigration journey of a young Adolphus Busch—he’s told “You don’t look like you’re from around here,” by evil nativist puritans, you know, just the sort of vicious microaggression Trump supporters commit against the brave, stunning progressives of today! Elsewhere, models got fat. Chipotle asked “Homo Estas?” Kendall Jenner solved racism with a Pepsi. A transgender bride sold insurance in the rain. Wasn’t it all just so ironic?

Many in advertising, myself included, were shocked by woke washing, interpreting it as a naked attack not just on capitalism but on everyday Americans. Why was men’s shaving cream forwarding far left gender theory? What does Nike, our beloved imperialist, have to do with racial justice? Those who believed in, even loved, capitalism’s cold indifference were awakened from our slumbers. So much for “Republicans buy Sneakers too,” which Michael Jordan said in 1990 just before he took over the world.

Almost everyone, regardless of political affiliation, was at least curious. What exactly was going on here? The mainstream media excused it as the intermingling of products with purpose, a practice which has existed in advertising since Edward Bernays sold cigarettes to women as feminist “Torches of Freedom” in 1929. But even right wing explanations—e.g. Boomercon op-eds in the Wall Street Journal—explained it away as “corporations yearning to be trendy” or “over-educated Millennial marketing people being myopic.”

https://youtu.be/SRjbXiwNVDc

No one came close to sufficiently explaining the phenomenon or its importance. The ubiquity of woke marketing goes against everything we believe(d) about America’s economy and values less than a decade ago. Our beloved brands launched what appeared to be unprovoked attacks specifically designed to undermine and alienate the belief systems of hundreds of millions of ordinary Americans. The fact that this is happening (and during the Super Bowl, no less) signals that something is very, very wrong.

Before you accuse me of histrionics, understand how pervasive the shift to woke marketing has been in the mainstream advertising world. The primary job of creative directors (basically hipster Don Drapers even as late as 2015) went from pitching branded variations of the Ice Bucket Challenge (I was one of them

) to venerating clients’ BLM Zoom backgrounds overnight. Every agency got hit at every level, and any outlier was instantly purged—see e.g. Brett Craig

(one of maybe two or three openly Christian Big Agency CCOs in the country who was canceled for a years-old email calling a black actor “urban.”) No longer do we sell clients’—large international corporations—products, we sell ideology, while still sort of loosely pretending to do the former.

Here’s an example. Clients have what are called brand guidelines decks containing not only their visual guidelines—logos, fonts, color hex codes, etc—but also their personality guidelines: mission statement, descriptive adjectives, brand “pillars,” tones of voice, etc. I recently received a 77 slide brand guidelines deck from a major brand packed full of brazen woke politics—centering underrepresented groups, girl bosses rock, hurray Latinx filmmakers, celebrate pride, etc. Really there’s no brand at all, just a reflection of sh*tlibbery. But then, on a single page after all that, there was a “What We’re Not” slide. The first bullet was “overtly political.” Followed by “preachy” and “woker than thou.” The cognitive dissonance was shocking. It just doesn’t make any logical sense.

So I ask again—what’s going on here really?

A profound shift requires a profound explanation. Put simply, what woke marketing reveals is that large international banks and corporations are intent on supplanting the sovereign states of the world; to become—whether publicly or not—the ruling party of a one world government. Not because they want to, but because they think they have to. If there can be a ruler of the world (which I would argue became a practical possibility with the advent of the internet) there will be a ruler of the world. If they don’t do it, someone else will. They’re saying to us, “look dude, this might not be a great idea, but I don’t see you comin’ up with anything better.” And they’re not totally wrong. What would we prefer—global communism? How about a global Islamic theocracy? Yeah, no thanks.

But that doesn’t change the fact that “they,” an intentionally-obscured network of global banks and corporations, are, in very actual fact, trying to take over the world. They want citizens to defect from nations and transfer loyalty to a unified global community—to become “global citizens” or, as I’m calling them, “consumer nationals.” And they’re doing this with the help of the corrupt leadership of the very states they seek to supplant.

What’s worse, many consumers want them to succeed. Those who don’t? They’ll happily leave us behind.

How Woke Ads Snuck In

Before we talk about what to do about this, it’s important to understand how we got here.

The unmooring of ads from their products began well before 2016. Miller Beer’s 1998 masterpiece Super Bowl ad Evil Beaver

, which many creatives consider the greatest TV ad of all time, epitomizes product-free absurdity. It sparked an absurdism trend in ads that lasted from Budweiser’s “Wassup,” through Geico Gecko, to its peak with Old Spice’s “I’m on a Horse.” These wonderful oddities, while random, still shoehorned in their products.

https://youtu.be/IB7OU0MlIvs

But in 2016 everything abruptly changed. Ads stopped being absurd in a funny way, and started being absurd in a political way—bizarrely obsessed with hot button issues that had nothing to do with the brands themselves.

Today, woke ads are both ubiquitous and deeply unpopular with almost everyone, including the intersectional populations they use as cannon fodder. This past June, the U.S. Marines celebrated Pride with rainbow bullets, the Audubon Society dressed up a drag queen as a flappy bird, and Postmates launched a “bottoms menu” for Pride so its customers could envision anal sex while eating. Reactions to these campaigns were uniformly negative, particularly from gay people. Even the most mainstream commentators grumbled “No-one asked for brands to replace governments and for ad agencies to replace NGOs!”

Regardless of negative pushback, not one woke advertiser faced serious economic consequences. Opponents promised to #JustBurnIt and #BoycottGillette. Conservative pundits presented data proving how ineffective the ads were. A conservative group called Consumers’ Research spent $1 million on videos calling out woke CEOs by name. And what happened? Nothing. The companies didn’t budge, and neither did their balance sheets. Bloggers searched, yearned, for facts and figures showing precipitous declines, but none stuck. No permanent dents in revenue. No shareholder revolts. Not one “learned their lesson.”

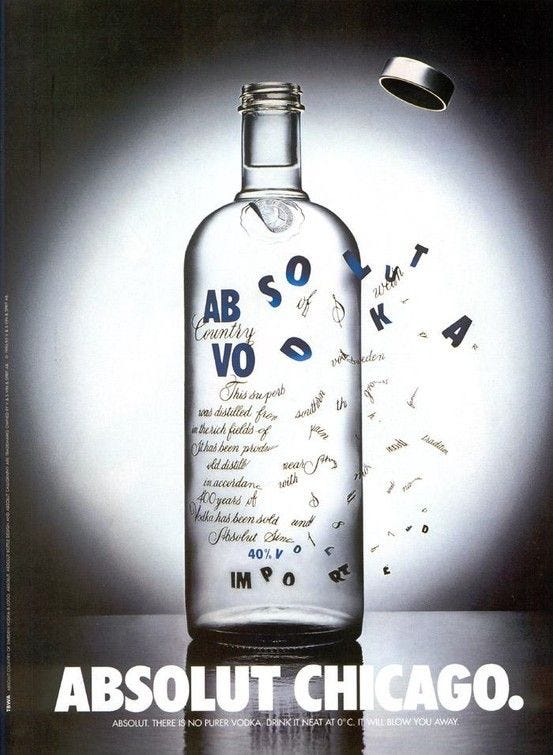

But at the same time, woke ads didn’t provide any positive benefit to advertisers either. Good advertising used to be able to change a brand’s destiny. Dos Equis’s “Most Interesting Man in the World” and Absolut’s Bottle Art campaigns multiplied revenue by several orders of magnitude and made the advertisers household names. But now? Extremely risky ads focusing on the most controversial possible political topics, broadcast via the most watched media channels, seemed to make no impact at all.

During Super Bowl LIV alone, eight brands—TurboTax, Sabra, Doritos, Pop-Tarts, Microsoft, Olay, Budweiser, and Amazon—ran ads about “genderqueer” and gay people. In other Super Bowl ads from 2017-2021, Mr. Clean embraced kink, M&Ms complained about mansplaining, Martin Luther King shilled for Dodge, and Keri Washington lectured babies about equality over a lullaby cover of Nirvana’s All Apologies for T-Mobile. Hundreds of millions of dollars spent. Zero impact.

“Evil Beaver” and “I’m On a Horse” were postmodern absurdism—they combined cultural references that didn’t make sense together but somehow worked. But absurdism left a void between ads and products, a void that was soon colored in with something else. The election of Trump and the wave of nationalism that swept the globe shortly thereafter sparked an extreme fear reaction among the aforementioned group of global banks and corporations—the advertisers we know and love. The advertising industry’s deep state—a very small group of white, over-educated, highly-political Hype Dads

—swiftly and unquestioningly did the bidding of these masters, even though it was very much against Hype Dads’ interests to do so, as we have seen time and again with woker-than-thou advertising executives canceled/pushed out/overruled by their new “diverse” employees. Even Martin Sorrell

, the undisputed king of advertising and very much a globalist himself, got cancelled.

The elites, fuming with reactive fury, showed their cards. The sudden robotic ubiquity of woke-ism in branding proves beyond a reasonable doubt that this is not a tactic or a trend. They are no longer interested in simply selling products, to Republicans or anyone else. They don’t want customers. They want citizens. Not advertisements, but flags. Rainbow ones. And that’s what they hoisted.

Why rainbow? Because that’s who’s buying. As I discussed in the first installment of this series

, woke identities are dependent identities; they require a “lifetime subscription” to the substances that corporations produce in order to “be affirmed.” Straight white male nationalists—or pretty much all right wingers—make poor consumers and troublesome employees, at least of the institutions that this particular set of banks and corporations controls. To find consumer nationals, corporations need to target anti-nativist populations whose loyalty is up for grabs.

But that’s not to say that nationalist types aren’t interested in buying anything at all. Throughout all of this, there are signs of a countervailing force, of new battle lines being drawn between globalists and a different sort of corporatocracy, one just as obsessed with sovereignty as the Enlightenment men who drafted the Declaration of Independence, even if that sovereignty will ultimately take the form of what many are calling a “network state

.”

Coinbase’s 2022 Super Bowl spot featuring a bouncing QR code screensaver became the most impactful TV ad in a decade. Made without an ad agency, it saved the company maybe $10 million. It was utterly devoid of purpose, besides to comment on purposelessness. It blew every other ad out of the water, generating 20 million unique site visits in minutes and boosting downloads 300%. No Super Bowl ad in years came close.

https://youtu.be/uJ9pNQrz0fA

The success of the intentionally banal Coinbase ad—which commented on the mechanism of propaganda itself—showed that there is a new kind of consumer reacting against mainstream messaging, and a new kind of company willing to serve them. This group not only has no tolerance for woke B.S., they’re actively looking for ways to undermine the global financial system: AKA crypto.

The Definition of Propaganda

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. ...We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.”This quote is from the book Propaganda by Edward Bernays, father of modern public relations. He pioneered consumer psychological manipulation and sleight of hand on a mass scale. He established the tricks that we take for granted today like the intertwining of celebrity endorsement, medical authority, press manipulation, and of course sex, with corporations and markets.

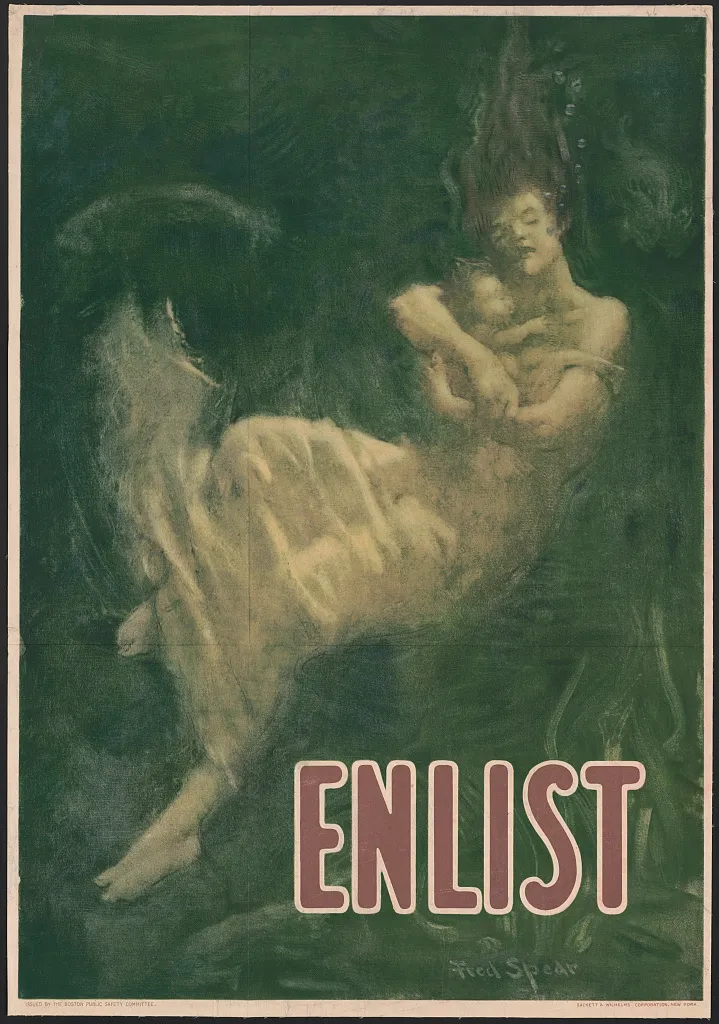

The word propaganda comes from the Catholic Church “propagating” its message in the 1600s. It used to mean “getting the message out,” but at the turn of the 20th century it acquired a more devious connotation. English and American WWI propaganda was heralded as the key to Allied success. England’s famous “Destroy this Mad Brute” poster and America’s Luisitania-related “Enlist” poster both manipulated emotion, suggesting that Germany was killing women and children, and you were letting it happen. The Uncle Sam “I Want You” poster was also born during this era.

At the time, Bernays was a young man working for the Committee on Public Information, an agency created by the Woodrow Wilson administration to foment domestic support for the U.S. in World War I. He took what he learned about emotional manipulation there, paired it with his uncle Sigmund Freud’s teachings about the subconscious, and offered his concept of “public relations” not just to governments, but to corporations too. This was the inciting incident on the path to consumer nationalism/corporate citizens.

One of Bernays projects was to inexorably tie capitalism to democracy. His propaganda included the General Motors Parade of Progress, a roadshow featuring a cavalcade of new inventions like the jet-engine, the microwave, and the television. Its purpose was to shift public perception towards corporations as the core driver of Americanism, not the state. Bernays also used corrupt doctors to incept the concept of the Hearty American Breakfast on behalf of Beech-Nut Packing, bacon sellers. His work fused consumerism, politics, and identity, transforming Americans from responsible citizens into passive consumers. They were no longer responsible for building their nation, like citizens, they were responsible only for signaling their happiness or unhappiness with what they were given, like consumers. Bernays achieved this, as his own daughter admits in Century of the Self, by manipulating people behind the scenes. By making them feel purposeful while slowly siphoning real purpose away.

Interestingly, the Nazis, who both mainstreamed Bernays' ideas and made them abhorrent, implemented pretty much everything he suggested besides keeping the puppet masters secret. To be clear, the Nazis absolutely relied on tricks and lies to enact the the Third Reich, including possibly burning the Reichstag, or at least using the incident to justify invading Poland. But unlike Bernays, the enactors of the propaganda weren’t hidden. Hitler and Goebbels were both thought to be responsible, and actually were responsible, for Third Reich propaganda. They were the ultimate self-doxxed shitposters. As it turns out, they may have been ahead of the curve.

Today, culture has surpassed postmodern (remixes and pop art) to what I term Deep Fried

(Miladys and Xxxtentacion). If PoMo is a collage of cultural references, Deep Fried is the same collage put through a copier 1000 times. In the meme context, Deep Fried means an image or video reproduced so many times that it becomes distorted. But it’s not just distorted—the copying process reveals the flaws of the copying machine, which creates a feeling of inhuman sinister-ness, similar to the uncanny valley. We’re moved by Deep Fried images because, in a way, we're seeing the machine itself.

Ads became disconnected from their products because we’ve arrived at a Deep Fried stage of advertising. Products and purpose had been copied on top of each other for so long that the mindsets of both consumers and sellers have been reset; the curtain pulled back. Today’s consumers glorify the propagandists that manipulate them, take for example the popularity of Mad Men or the Hunger Games, or the devoted following of Gary Vee, all of whom obsess over the undeniable effectiveness of propaganda.

Bernays glorified invisibility. So what happens, Mr. Bernays, when the voter, the consumer, knows they’re being manipulated, and doesn’t care? The leader, the marketer, the seller of things or ideas—if his job is no longer to “manipulate this unseen mechanism of society,” what’s left for him to do?

One of the first people to figure out the answer was Jeff Bezos. Amazon Prime didn’t make much sense at first. Why was the online everything store suddenly selling content subscriptions and free shipping? What a weird combo. But Bezos saw how customers had changed. Bernays had turned citizens into customers, but now customers wanted to be citizens…of pretty much anything. Bezos saw Netflix lovers not as customers buying a product, but as subscribers to a lifestyle. So he whipped up another Netflix and grafted it onto Amazon—hello Amazon Prime. Unlimited streaming movies! Original TV shows with your favorite stars! The perfect flypaper for a new generation of customers ready for a different, more transparent kind relationship with their corporate overlords.

Tellingly, Bezos had always eschewed advertising—in 2009 he said it was “the price you pay for having an unremarkable product or service”—until he abruptly changed course and became the largest advertiser in world history. He realized that when Amazon advertises, it’s actually not advertising a product or a service. It’s recruiting citizens. People who are “taxed” in exchange for rights and privileges. Then he bought Whole Foods.

This is the second part in a four part series called The Road to Consumer Nationalism. Part one is here

. Part three will be published next week.